The 80-20 rule: the Pareto principle

The Pareto principle is also known as the Pareto effect or 80-20 rule. It is named after the Italian inventor Vilfredo Pareto. At the beginning of the 20th century, Pareto, who also worked as an engineer, sociologist, and economist, carried out some studies. These dealt with the distribution of national wealth in Italy. Pareto's research revealed that one fifth, or 20 percent of Italian citizens, had about 80 percent of the state's assets. From this realization, Pareto stated that banks should essentially focus on the wealthy 20 percent of Italians in order to be more efficient and make more profit. Conversely, the banks would then provide 80 percent of the population with only a fifth of their time spent.

What is the 80-20 rule?

The Pareto principle represents the unequal distribution and lack of balance between resource input and return. This can also be illustrated in other areas:

- Sales: 20 percent of products or customers generate 80 percent of sales

- Storage: 20 percent of the products occupy 80 percent of the space

- Internet: 80 percent of online data traffic takes place on 20 percent of websites

- Road traffic: 20 percent of the roads are used for 80 percent of the traffic

- Phone calls: 80 percent of calls are made with 20 percent of the stored contacts

However, the 80-20 rule is best known for its application in time management. With the right prioritization you can do 80 percent of the work with by spending 20 percent of the time.

The Pareto principle states that by investing just 20 percent of effort one can reach 80 percent of the overall result. For the remaining 20 percent of the result, 80 percent input is needed. This is why it’s often referred to as the 80-20 rule.

Purpose and advantages of the Pareto method

The purpose of the Pareto method is to achieve great success with the least possible effort. After all, a lot of time is often invested in tasks that have only a low priority. However, with the right priorities and better time management, you can work more efficiently and purposefully. Especially in work areas with strict deadlines, the Pareto principle helps in focusing the workload correctly in order to complete the tasks in the given time. The 80-20 rule is also often used together with other time management methods, such as the Eisenhower principle.

Disadvantages and dangers

There are some common mistakes that are often made in connection with the Pareto principle. For example, it is often misinterpreted that with 20 percent of the invested time or effort, you can also achieve the 80 percent return that you would achieve with your usual effort. This makes no sense, however, as then 100 percent would be achieved with 20 percent effort. This is a misinterpretation in which the individual percentages are simply added up to 100 percent, although they stand for different aspects. However, expense and income are not the same, and cannot simply be added together. In order to generate the full 100 percent return, the expenditure must also be 100 percent. The misinterpretation described above quickly leads to over-optimistic assumptions as to which goals can be achieved with how much effort.

But even if the basic principle itself has been understood, the conclusion that 80 percent of the possible performance is due to 20 percent of the effort can lead to a reduction in all tasks to only 20 percent. After all, there are a number of tasks that do not contribute directly to the actual goal, but must nevertheless be completed. This includes, for example, writing and replying to e-mails. E-mail correspondence usually contributes little to a company's success, but not responding to business e-mails at all would have serious negative consequences for the company (as would neglecting the accounting – even if the accounting department itself does not generate any profits). These absolutely necessary, but seemingly unproductive tasks can be optimized by keeping the expenditure for them as low as possible.

In addition, the Pareto principle can lead to certain negligence, as the majority of tasks are considered to be of little importance. Only those who dedicate themselves to their tasks in a conscientious, concentrated, and structured manner can also achieve 80 percent of the results with 20 percent of the work – it is quite unusual to pull this off.

Importance and use of the 80-20 rule

The 80-20 rule can be applied in many ways: It can be used for better time management in private life, during studies, and at work. By making oneself aware of which work makes up the majority of the yield, one can prioritize individual tasks better. The Pareto principle helps to decide which work must be completed first.

When can the Pareto principle be applied?

The Pareto principle can theoretically be applied to all areas of life - in school and academic education, as well as in everyday life. However, the 80-20 rule is most often associated with working life, and this is when you’ll have to meet deadlines frequently. Even in private life there are daily tasks that have to be completed as efficiently as possible within the shortest possible time.

Pareto principle: example of everyday use

If your family or friends announce a spontaneous visit, there may be little time to tidy the home. If it normally takes three hours to complete all household tasks, a visit announced at a late stage can only take an hour and a half. For this reason, taking into account the Pareto principle, you should first occupy yourself with the tasks that have the greatest effect on the well-being of the guests. This includes, for example, removing objects and clothes lying around, stowing the dirty dishes in the dishwasher and wiping the tables. Since living rooms, guest rooms, and bathrooms will be visited more frequently by the guests than the cellar, you should concentrate on them.

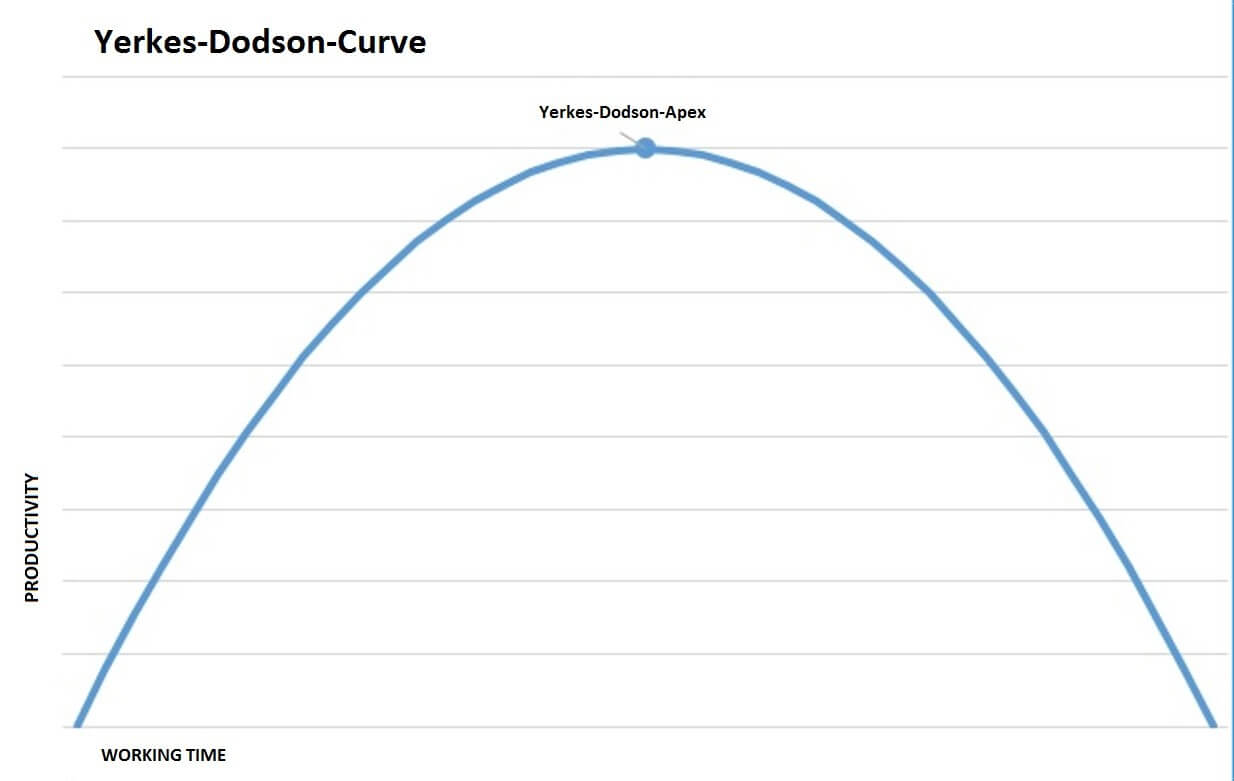

80-20 rule and the Yerkes-Dodson curve

Similar to the Pareto principle, the Yerkes-Dodson curve also deals with the relationship between input and productivity. This curve was named after the psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson. Their research has shown that productivity improves with increasing commitment. But this is only true up to a certain point, the point at which an increase in performance results in a reduction in productivity. This point is also called the Yerkes-Dodson apex.

The Yerkes-Dodson curve roughly corresponds to an upside-down U shape. If you continue to invest time and effort permanently after reaching the optimum performance, productivity drops: The higher pressure and the resulting stress then cause a performance drop, which leads to worse results. Similar to the 80-20 rule, the Yerkes-Dodson curve states that only a certain amount of effort results in the highest productivity. Higher percentages of effort, on the other hand, don’t yield much in terms of productivity.