How to remove personal information from Google

In May 2014, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in Luxembourg issued the “right to be forgotten”. This stipulates that search engines such as Google must remove search results if they involve sensitive personal data which is incorrect, excessive, outdated or has become irrelevant.

How to delete personal information from Google

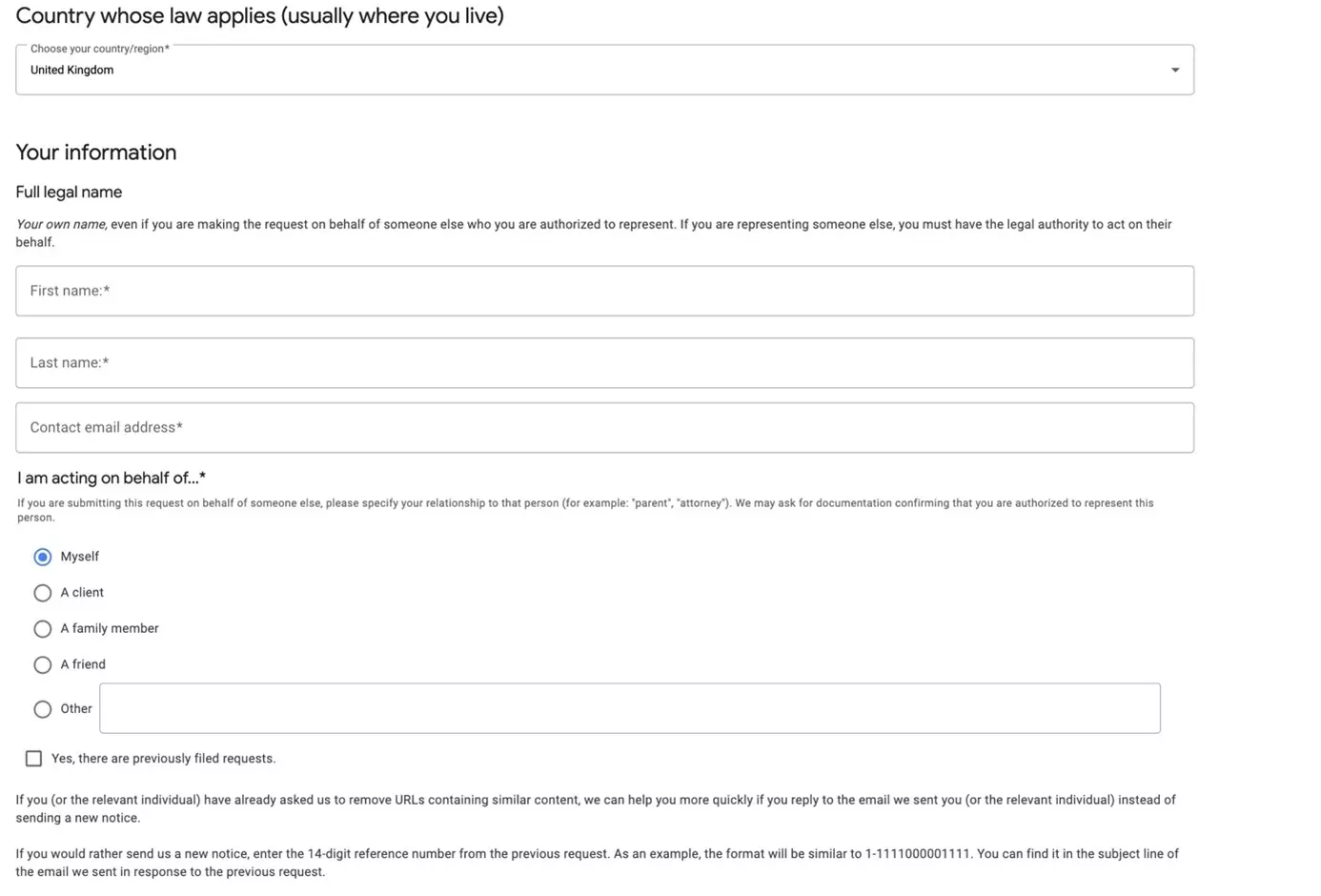

If your request falls under the right to be forgotten, you can get started with the following form on Google.

Step 1: Open the personal data removal form in Google.

Step 2: Enter the country where the law is applied. In most cases, this is the country where you reside.

Step 3: Now enter your name and email address. You can also submit the form on behalf of another person. Simply specify your legal relationship to the other person.

Step 4: Now enter the websites you wish to have removed from search results. To do this, provide the URL that you want removed from Google search results If you want to report multiple addresses, use multiple lines, with one URL per line.

Step 5: Specify why the link(s) should be removed from search results. You must enter a reason for each URL you specify. Again, use one line per reason.

Step 6: Now enter the name under which you (or the person for whom you’re making the request) can be found on Google.

Step 7: Finally, confirm you agree to the data processing for this request and that all data provided are correct. Now enter the current date and your name, and then submit the application.

To remove personal information from Google search, the search giant provides multiple forms. These differ according to the reason for entry removal. In addition to the right to be forgotten, outdated data or non-consensual pornography may also be removed. Google has created the help page “Remove your personal information from Google” where you can find links to the relevant forms.

Removing personal information from Google search doesn’t mean your data has disappeared from the internet entirely. The deleted entries are only the search results, i.e., the links that appear in search engine results lists. The information itself is still available but isn’t as easy to find. You should remove the information from other search engines as well. Bing also provides a form for deletion requests.

Why is Google required to delete entries in the EU?

In 2014, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in favor of a Spanish citizen who had asked Google to delete links to articles about him. The information in the newspaper article in question had long been out of date and the plaintiff felt it was damaging to his reputation. The ECJ agreed and Google had to remove the links.

As a result, the right to be forgotten was incorporated into the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Article 17 of the GDPR states that people have the right to erase their personal data from the internet to prevent its further dissemination.

Technically, the U.S. does not recognize the right to be forgotten as it interferes with first amendment rights and freedom of expression. However, in April 2022, Google added an option for U.S. citizens to request removal of their personal information.

What type of content can U.S. citizens request Google to delete from search results?

Google isn’t obliged to comply with every deletion request. Especially in the case of public figures (such as politicians or other celebrities), society’s interest in information may outweigh the right to be forgotten. It should also be noted that this right only applies to people; links to information about companies aren’t applicable.

U.S. citizens can ask Google to remove:

- Personal information such as phone numbers, email addresses or physical addresses

- Handwritten signatures

- Intimate personal or non-consensual images/photos, images of minors

- Fake/irrelevant pornography

- Exploitative content

- Personally identifiable or doxxing content

Can you delete entries yourself?

You cannot remove links yourself. To remove links, you must submit a link deletion request to Google. As such, waiting times are to be expected as Google reviews your request.

However, you also have the possibility to contact the operators of websites directly. Once the website operator removes the requested information, Google search results will update accordingly. To speed up the process of changing the search results, you can use the Google request form to remove outdated content.

If you want to remove false claims about your company, you can also make a request to delete Google reviews. In addition, you can also delete your Google account.